August 12 marks International Youth Day, which in 2015 focuses on civic engagement, because the “engagement and participation of youth is essential to achieve sustainable human development. Yet often the opportunities for youth to engage politically, economically and socially are low or non-existent.”

There are, I believe, at least three reasons.

First, human development is – by definition – forward looking. And young people have furthest to look forward. I remember an Australian professor once remarking that she preferred to think of the young not simply as human beings, but as human becomings. The importance of what she meant was clear in last year’s Human Development Report (HDR) – which focused on vulnerability and resilience. The report considered how people’s vulnerabilities change over the course of their lives and presented a range of evidence about how disadvantage early in life – even in the first 1000 days - creates gaps that worsen over a lifetime. Disadvantaged children are on track to become the youths who do poorly in school or drop out. In the workplace they perform the most menial work and earn the lowest wages (and these are topics that will be covered in this year’s forthcoming report on Work). And when these young people have children, a cycle of inherited poverty begins—and is repeated across generations. This cycle must be broken during childhood, indeed early childhood development is now recognized as a very important component of development.

Moreover, youth is a time for transition: from childhood to adulthood, from school to work. But transition points are, as the 2014 HDR argued, particularly vulnerable moments: setbacks here can be especially difficult to overcome, and scar a young person’s chances for a better life. In her contribution to the 2014 report, Abby Hardgrove and her colleagues argued that “policies aimed at preventing problems facing young people need to engage with context” and “multiple vulnerabilities, stemming from poverty, inequality, social exclusion and hazardous environments, reinforce and overlap with one another, constraining the development and well-being of young people”.

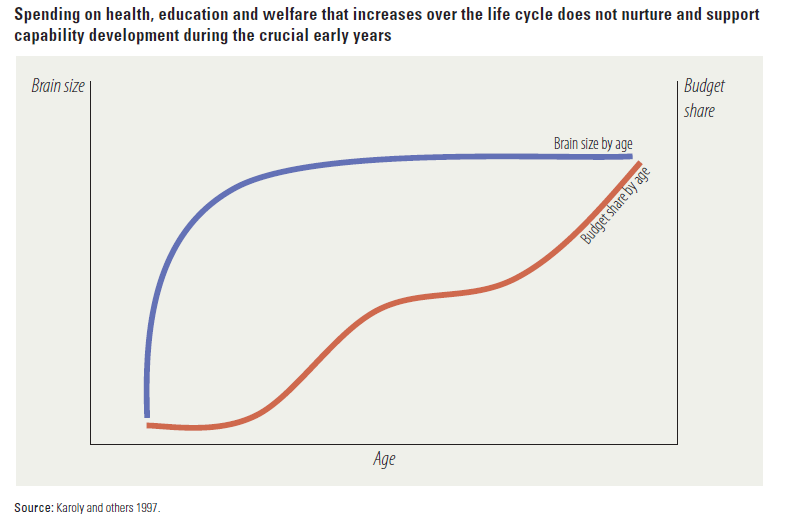

Human development analysis can help us to rethink this. The 2014 HDR asked why, for instance, is government spending on different age groups so often out of line with people’s physical development? The graph shows that brain growth is extremely rapid during the earliest years and then tends to flatten, while public expenditure is lowest in these early years and rises thereafter. Spending on health, education and welfare does not, the report argued, nurture and support development during the crucial early years.

The second reason for the interest is that, through demographics alone, the fate of young people is tremendously important to human development. Not only do the world’s youth (15-24 year old) represent almost a fifth of the planet’s population but they are a group found predominantly in the south: some 85% of young people today are in developing countries and in many places, young people — especially girls — still don’t have access to basic education, reproductive health services and employment opportunities.

And the third reason is that many development policies have an impact best understood over the longer term. In other words, today’s policies are often most likely to affect the adults of tomorrow. Voice and participation are a key part of the human development approach and important for long term policy making. It is vital, for human development, that young people are given a voice in the development processes that are seeking to shape the worlds they live - and will grow up – in.

This is exactly what this year’s International Youth Day is calling for and NHDRs provide a mechanism for doing this. Indeed several reports have focused on youth in recent years and have been successful in engaging young people, often in innovative ways.

One of the better-known examples is from Turkey, where the 2008 NHDR “Youth in Turkey” involved young people in many ways, especially the research: 3,000 youth took part in a survey, and twenty eight focus groups were organized. The report was particularly influential, generating more than a thousand news reports that placed youth issues on the national agenda. Some of the Youth NGOs who participated established a platform to continue the work on – and advocate for - a youth policy. This, along with Turkey’s first ever Youth Ministry, was introduced by the government a few years later.

While several reports have won awards it is important to remember that considering development from a youth perspective is not always straightforward (see the Human Development Report Office guidance on working with youth in NHDRs). Indeed, even defining exactly when someone should be considered “young” can be tricky and varies between reports.

Listening to the views of young people will almost certainly require an investment of time and money. And so development policies that are formulated with the input of young people will cost more to develop. But those policies will almost certainly work better. And they are bound to last longer: because today’s youth will be the opinion leaders of 2030. Let us remember that on International Youth Day.

Jon Hall

Jon Hall is a policy specialist in the Human Development Report Office

Image: Dani Alvarez via Creative Commons