Earlier this month I spoke at an event to launch a new book - “Human Development and Global Institutions: Evolution, Impact, Reform” - by Richard Ponzio and Arunabha Ghosh (Routledge, London). It provided a welcome opportunity to reflect on the role human development has played in shaping global development, including the global development goals, for which I believe it is the background.

After spending more than 50 years in development - working for the UN, USAID, the private sector and in think tanks – I firmly believe that public servants in national and multilateral governance are often highly capable, despite what some may say. But I also recognize that rarely are there real intellectual centers in public service that move very large global issues forward.

In the lifetime of the UN, there have been two times when intellectual centers addressing major global issues led to a sea change in how the world works.

One such time was in the late 1940s when a number of Nobel prize thinkers created national accounting, like the Gross Domestic Product (GDP), and established the post-World War II international trade regime.

The second such time started in 1989 with the beginnings of the Human Development Report Office.

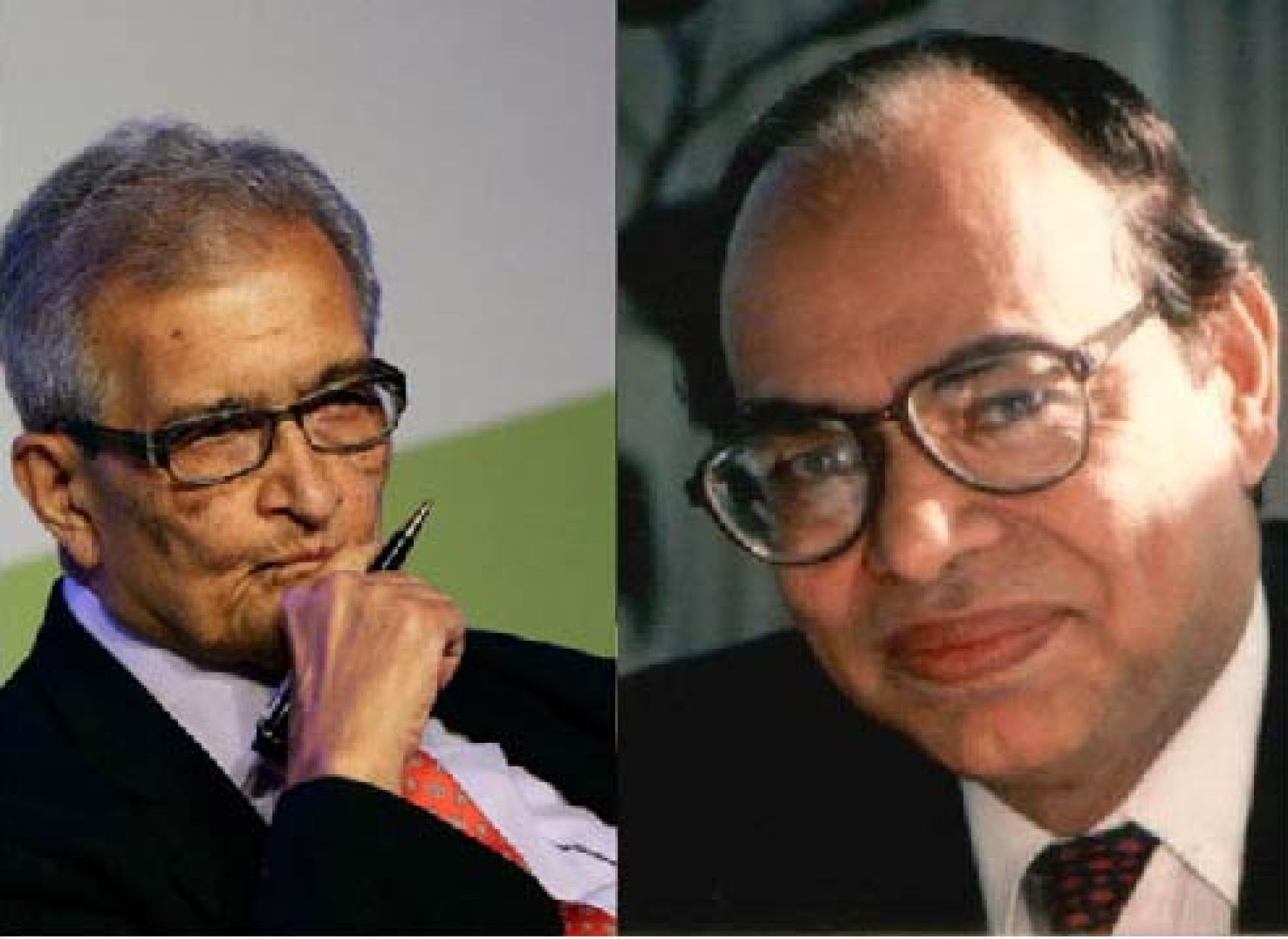

The Cold War ended that year and many things seemed more possible. Mahbub ul Haq, Amartya Sen, Paul Streeten, Richard Jolly and Frances Stewart, and others said, in essence, that the work of the first intellectual group in the late 1940s was useful, but GDP didn’t tell us how people really were doing nor what their social and economic status should be.

This was a well-considered long-term interest of Mahbub’s. I first heard about him in 1969 during a meeting in New Delhi when Dudley Seers, then head of the Institute of Development Studies at Sussex, said there was this chap from Pakistan who urged development to stand on its ear, moving from top-down theories of development to bottom-up development. I would meet with Mahbub in the early 1970s when he was re-engineering policies in the World Bank towards poverty and I was working with others in USAID to do the same. But his work at the UN in the early 1990s led to something much bigger.

What made this second wave of intellectual might so different from the first wave?

First was the attempt – with Human Development - to be prescriptive across the whole field of development.

Second, in 1990 a new UN strategy was pioneered by Jim Grant, then head of UNICEF: he married great policy with law (the Convention on the Rights of the Child) and high stakes politics (The World Summit for Children). A very different approach to the UN’s then common practice of issuing rather hollow declarations that often weakened the UN’s credibility. The result? For the first time, global heads of state met and acted to advance the human condition.

That formula - the UN articulating policy, and fostering law and high level political agreement - empowered the UN to have much more influence and impact. It led directly to the Millennium Development Goals and the Sustainable Development Goals. Moreover, it forced the UN’s often rather dysfunctional family of separate organisations to work together for common purpose, enabled by a real board of directors, the Chief Executives Board, holding agencies accountable for follow-through.

From the mid-1990s, in response to UN system-wide work I was doing, for the first time the World Bank started to attend the UN’s heads of agencies meetings. All this led to growing credibility for the UN and in time gave it the standing to effectively broker the world’s first agreement with real hope for the environment.

Now we have a UN that is seen as legitimate to guide its members on social and economic issues, to gradually be more active on human rights and to act much more aggressively to help solve political issues. And the human development reports have played a major part in this.

Can we imagine a third wave of intellectual leadership at the UN? Is there another possibility that a future Tinbergin or Mabhub ul Haq will be able to lead a critical mass of intellectual power within the UN? The answer is Yes and No.

Yes, the UN could always engage the best available talents, could stop appointing second rate advisory groups, and consistently hire stellar leaders to run its agencies.

But No, the way the UN’s intellectual centers operated the last two times we had great centers, are sub-optimal for the 21st century.

If we are so lucky as to have a next nexus of high level intellects working together, it should operate very differently. Its expertise will be to identify really important questions, and then to network like mad. It would do that through open source competitions, partnerships, alliances and other ways of engaging large numbers of thinkers, social entrepreneurs, and program managers. And that will bring the creativity and, importantly, more constituency and support for global and UN actions on the questions the next intellectual center raises.

We need to help the UN to be a modern leader of thought, gathering the best ideas, promoting the best solutions and in the process creating pluralistic global constituencies to solve the major human development challenges of the years ahead. These, I believe, will be the hallmarks of the next UN intellectual leadership.

About the author: Robert Berg has led a distinguished career of service in government, civil society, and the private sector. From 1965-1981, he was with USAID where he helped draft the landmark Basic Human Needs legislation and founded USAID’s Office of Evaluation. He has served as senior advisor to four parts of the United Nations: UNICEF, UNESCO, UNDP, and the Economic Commission for Africa. In these assignments he helped to carry out the first global summit to advance humanity, The World Summit for Children, and initiated the first U.N. system-wide program substantive endeavor. He has also chaired a donor OECD grouping, was Senior Fellow at the Overseas Development Council, Senior Advisor to the World Federation of United Nations Associations, and was President and then Chair of the International Development Conference. Currently he is Chair of the Alliance for Peacebuilding and is Advisor to the Board of the World Academy of Art and Science and a Distinguished Fellow at the Stimson Center.

The HDialogue blog is a platform for debate and discussion. Posts reflect the views of respective authors in their individual capacities and not the views of UNDP/HDRO.

HDRO encourages reflections on the HDialogue contributions. The office posts comments that support a constructive dialogue on policy options for advancing human development and are formulated respectful of other, potentially differing views. The office reserves the right to contain contributions that appear divisive.