A decent and dignified life for all 7.5 billion people in the world is possible. The world is not short on technological and financial resources. And so everyone could have a quality education, a secure income, access to good healthcare and live in a clean and safe environment. Why should anyone be hungry when we know that reducing food waste, changing diets and increasing yields could provide food for double the current population? Likewise, if the world can spend some 1.7 trillion USD on the military each year, generating the estimated 1.4 trillion USD required annually to finance the SDGs is certainly within the realm of the possible.

So why are 1.5 billion people still multidimensionally poor? Why are deprivations in fundamental conditions of life like food, decent work and clean water so prevalent across many societies? The reason is not merely technical or financial. It is linked to deeply rooted social and political inequalities. Discriminatory laws, exclusionary social norms, and imbalances in opportunities for political participation and influence stand at the root of deprivation and disadvantage. They perpetuate divides where women have fewer choices than men, the poor have fewer choices than the rich, migrants have fewer choices than citizens, and some ethnicities have fewer choices than others.

For example, traditions of child marriage, laws that require approval from husbands to work, and norms that distribute the bulk of unpaid care work to women limit the choices women have and curtail overall human development outcomes across societies. Likewise, when one ethnicity, religion or class monopolizes the political landscape, policies are less likely to address the needs of underrepresented groups. In certain contexts – Bosnia and Herzegovina, Northern Ireland in the UK, South Sudan, and Syria to name a few – such inequalities erupt in violent conflicts that further undermine human development progress.

Political and social barriers will not be easily overcome. Especially if we do not recognize them as central and highly complex impediments to progress. A key challenge today is that existing divisions may be deepening. The world in which people make decisions is global and competitive with multiple pressures from volatile financial systems, demographic shifts, environmental degradation and climate change, and new technologies and systems of work. The pace of change is rapid and unpredictable. Protecting or securing access to jobs is a foremost concern for many people. In this context, social cohesion, mutual respect and tolerance of differences can be strained or breakdown altogether morphing into xenophobia, nationalism, discrimination and sometimes violence. The exclusion that results can be intentional or unintentional but with the same results – some will be more deprived than others and all people will not have equal opportunities for realizing their full potential.

Social and political inequalities can reinforce inequalities in basic dimensions of human development that can in turn further reinforce social and political divides. The latest figures on income inequality indicate that 8 men hold as much wealth as the poorest half of the world’s population. Those at the top of the distribution have the resources to enjoy more advanced healthcare, more secure livelihoods, better quality education, and – perhaps most importantly – more political influence. They have the capacity to influence institutions and rules like tax policies and public spending programmes in their favor. Others lack resources to send their children to good schools, to access regular medical care and – when traditional organizations like unions decline and rights to free association are not protected or respected – they lack political leverage.

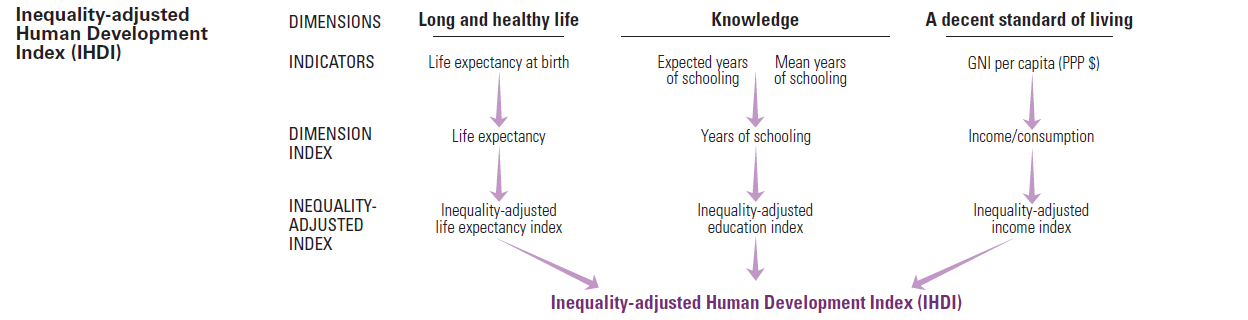

Inequalities in education (using the Atkinson measure of inequality where 0 represents equality) are even higher globally than income inequality (see figure). Inequalities in education are most extreme in South Asia, the Arab states and Sub-Saharan Africa with inequalities in income remaining higher in Latin America and the Caribbean and East Asia as well as in OECD countries. Education can be a means of breaking down social and political barriers, increasing political participation, and improving upward mobility. When people cannot read or write, their knowledge about legal rights and their abilities to appeal against unfair treatment are limited. And a lack of education, especially for girls, can perpetuate patriarchal norms.

|

So should we be pessimistic? Not necessarily. But we must be realistic about the barriers that need to be addressed to advance universal human development and we must look beyond technology and funding for solutions. A transformative shift in social and political inequalities is in order including: (i) overcoming intolerance of diversity and building respect for the values and aspirations of others (as with increasing the rights of migrants or reducing social norms that discriminate against women); (ii) broadening political representation and public dialogue (as with quotas for political participation of under-represented groups); (iii) increasing the bargaining power of marginalized and excluded groups (as with upholding rights of freedom of association and making public investments in quality education); and (iv) shifting from a national or community based identity to self-identification as part of a global community (as with campaigns on the importance of global public goods).

Transformative shifts do happen. Social attitudes toward members of the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex community have become more tolerant in all regions since the 1990s and antidiscrimination laws have increased. Child marriage is declining, paternity leave is offered in more countries and businesses, and women are filling more parliamentary seats shifting gender inequalities in human development. Ethnically diverse countries from Botswana to Canada and Malaysia have minimized political inequalities and fostered inclusive institutions. Indeed, progress is possible, but we must be realistic about the nature of the barriers.

1. Foley, J. (2014). A five-step plan to feed the world. Natl Geogr, 225(5), 27-60.

2. Calculations based on 2015 data from World Bank World Development Indicators.

3. Schmidt-Traub, G., & Shah, A. (2015). Investment Needs to Achieve the Sustainable Development Goals. Paris and New York: Sustainable Development Solutions Network.

4. Hardoon, D. (2017). An economy for the 99%: It’s time to build a human economy that benefits everyone, not just the privileged few. Oxfam.

The HDialogue blog is a platform for debate and discussion. Posts reflect the views of respective authors in their individual capacities and not the views of UNDP/HDRO.

HDRO encourages reflections on the HDialogue contributions. The office posts comments that support a constructive dialogue on policy options for advancing human development and are formulated respectful of other, potentially differing views. The office reserves the right to contain contributions that appear divisive.

Photo: (cc) Wayne S. Grazio Aka Fotograzio