Few, if any, statistical constructs have had a greater influence on the modern world than Gross Domestic Product (GDP). And 2014 marks the eightieth anniversary of its creation.

As every economist knows, GDP summarizes total economic activity. It was developed by Simon Kuznets, a Russian-American economist and statistician, as a way to better understand the American economy during the great depression. Not only was Kuznets a brilliant economist (he went on to win the Nobel Prize in 1971), he was also an astute judge of humanity, or at least the potential for people to misuse numbers: when he introduced GDP to the US Congress he warned specifically against using it as a measure of wellbeing: “the welfare of a nation can”, he wrote, “scarcely be inferred from a measurement of national income”. And this is because, as hopefully every economist also knows, it is easy to construct examples of undesirable social or environmental phenomena (crime sprees, oil slicks or hurricanes for instance) that can generate both an increase in GDP and a decrease in wellbeing.

But despite Kuznets’s warnings, in both the US and many other countries, the pursuit of economic growth and a rising GDP quickly became a dominant mantra of policy making.

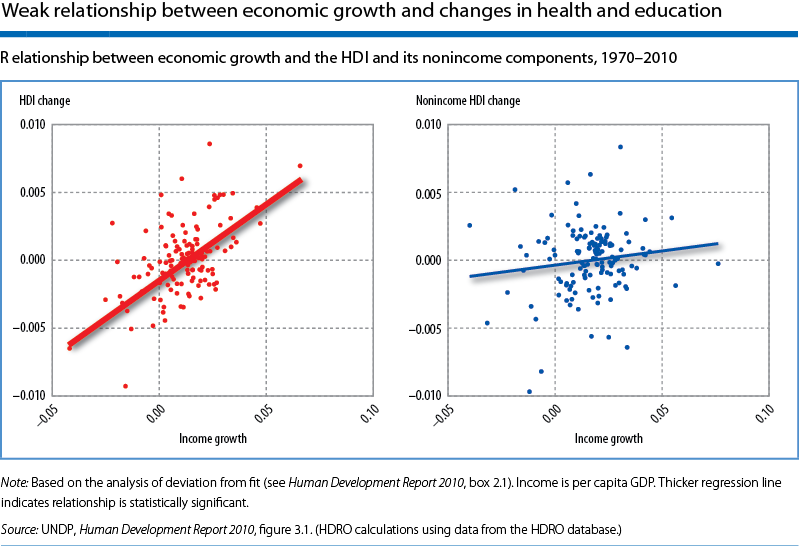

Eighty years on there are ever more – and ever more influential - voices calling for better metrics of progress to guide decision making. These voices recognize that what we measure affects what we do. They argue that we need metrics that focus first and foremost on people’s lives, and which recognize that economic growth is a means to an end, not an end in itself. UNDP is proud to have played a leading role in this global conversation, through the introduction and championing of global, regional and national human development reports and the Human Development Index. Our work has helped change the development debate. No longer is it automatically assumed that growth and development are synonymous, or that growth is a prerequisite for development. As the 2010 Human Development Report showed, there are different paths to development and increases in health and education are not always correlated with economic growth.

The left panel above shows a positive association—though with substantial variation—suggesting that growth and improvements in human development are positively associated. Remember, however, that income is part of the HDI; thus, by construction, a third of the changes in the HDI come from economic growth, guaranteeing a positive association. A more useful exercise is to compare income growth with changes in the non-income dimensions of human development. The 2010 HDR did this using an index similar to the HDI but calculated with only the health and education components indicators of the HDI to compare its changes with economic growth. The non-income HDI is presented in the right panel of figure 3.1. The correlation is remarkably weak and statistically insignificant.

Previous studies have found the same result. One of the first scholars to study this link systematically was US demographer Samuel Preston, who showed that the correlation between changes in income and changes in life expectancy over 30 years for 30 countries was not statistically significant.

A key facet of human development philosophy is giving people more control over their lives. Some 800 national human development reports have championed this approach, emphasizing the importance of asking citizens what they see as important. And I hope this blog will also play a part, giving anyone a chance to give their views about what they see as important in this most important of topics.

It is also important to remember that human development is an open-ended concept that encompasses many aspects of life, and certainly goes well beyond our health, education and income, as measured in the HDI. This blog will also offer a means by which we can all discuss the many broader issues that together determine the development of humanity.

Human development has been defined as giving people the chance to live lives they have reason to value. It seems that US Senator Bobby Kennedy had a similar idea in mind when he spoke so eloquently in 1968 about the dangers of paying too much attention to national income, concluding that national income does not “allow for the health of our children, the quality of their education, or the joy of their play. It does not include the beauty of our poetry or the strength of our marriages; the intelligence of our public debate or the integrity of our public officials. It measures neither our wit nor our courage; neither our wisdom nor our learning; neither our compassion nor our devotion to our country; it measures everything, in short, except that which makes life worthwhile”.

The Senator’s words ring true today. We may have eighty years’ wisdom about the shortcomings of GDP, but it’s a number that still carries far too much influence with many decision-makers. The need for discussion and debate about human development has never been greater and I am looking forward to hearing what you think.

Khalid Malik is the Director of the Human Development Report Office.

The HDialogue blog is a platform for debate and discussion. Posts reflect the views of respective authors in their individual capacities and not the views of UNDP/HDRO.