A starting point of the upcoming global Human Development Report (HDR) is that work is intrinsically linked to human development. One’s ability to choose whether to seek a paid job, and what type of work to do, is an important expression of agency, and so fundamental to human development.

Too often, however, this freedom is not open equally to women. Gender gaps arise in multiple forms, and are persistent. Indeed over the past two decades, female labor force participation rates globally have fallen, from 57 to 55 percent. Women and men tend to work in different sectors, occupations and firms. Women consistently earn less than men, largely because of their concentration into low paid activities and lower access to productive inputs.1

In many countries, there has been remarkably little change in the gender balance of some of the most common occupations over several decades. As one focus group participant in Niger explained recently, “Men have their occupations, women have theirs. It’s like that since childhood, it’s our heritage.”

Women have moved into new fields in management and professional occupations, but their comparative concentration in healthcare, care work, and education and their underrepresentation in other sectors continues. Trends in the US are sobering: women comprised more than 90% of pre-school and kindergarten teachers, hair dressers and dental hygienists in 1972. They are more than 90% now. Men’s share of nursing has quadrupled since 1972, but nine in ten nurses are still women.2

This picture is especially remarkable given the major gains in education that have been achieved over the same period.

What stands in the way of the expansion of women’s economic opportunities? Adverse norms and overlapping constraints are major obstacles. As farmers and entrepreneurs, they do not enjoy equal access to credit, land or bank accounts.

Biased norms restrict opportunities by establishing gender roles early in life that dictate the use of time and limiting girl’s expectations. This helps to explain why progress in overcoming gender gaps in one area, such as school enrollment, may not expand a woman’s economic opportunities if social norms or gender-biased regulations limit her activity.

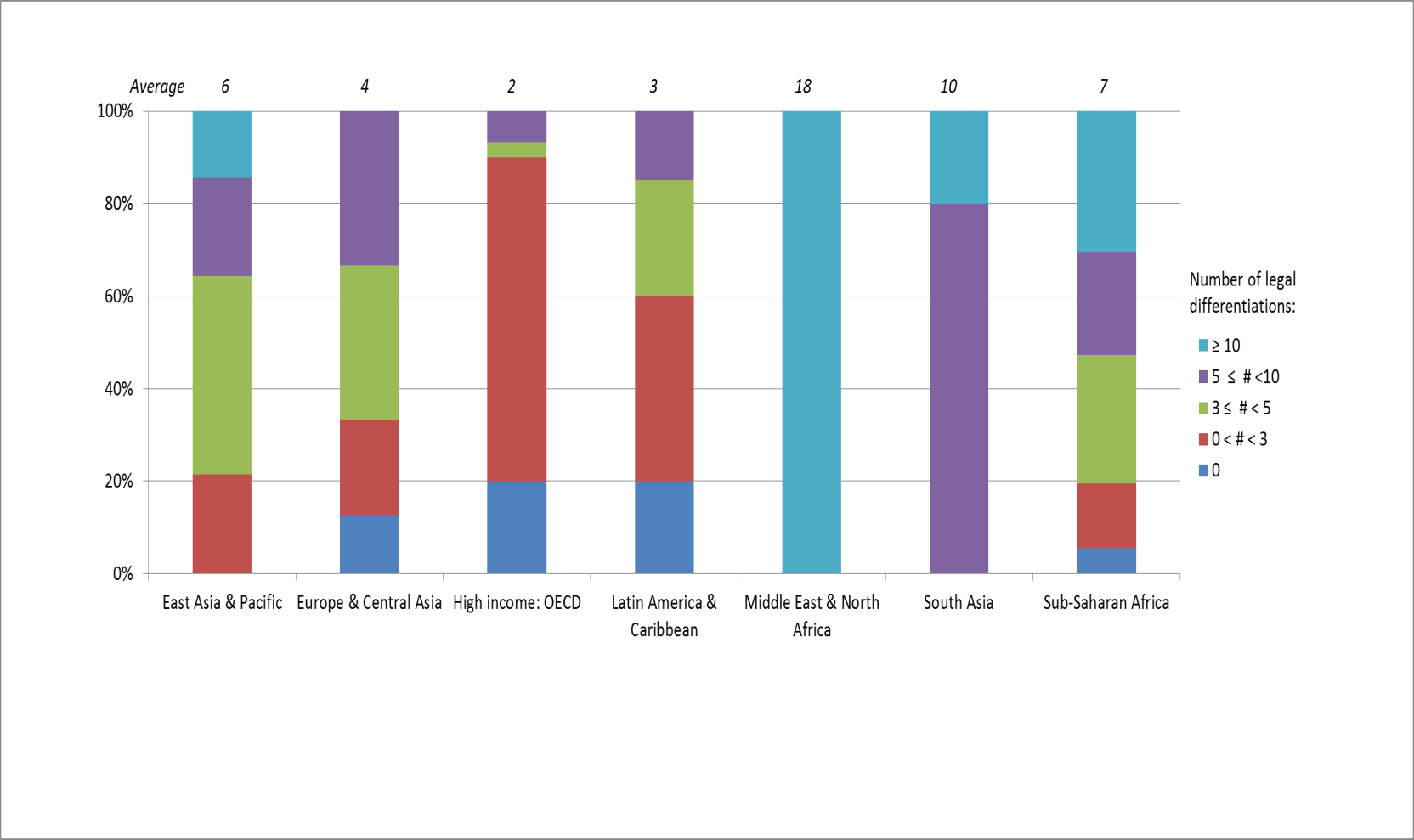

Legal discrimination remains a remarkably common barrier to women’s work. Across 143 economies in 2013, 128 had at least one legal difference in how women and men are treated; 56 countries have more than five such barriers, and 28, more than ten. These barriers include restricting women’s ability to access institutions (such as obtaining an ID card), own property, build credit, or get a job. In 15 economies, husbands can prevent their wives from working.

Formal Constraints to Women’s Economic Empowerment, 2013

Source: Women, Business, and the Law, 2013, IFC

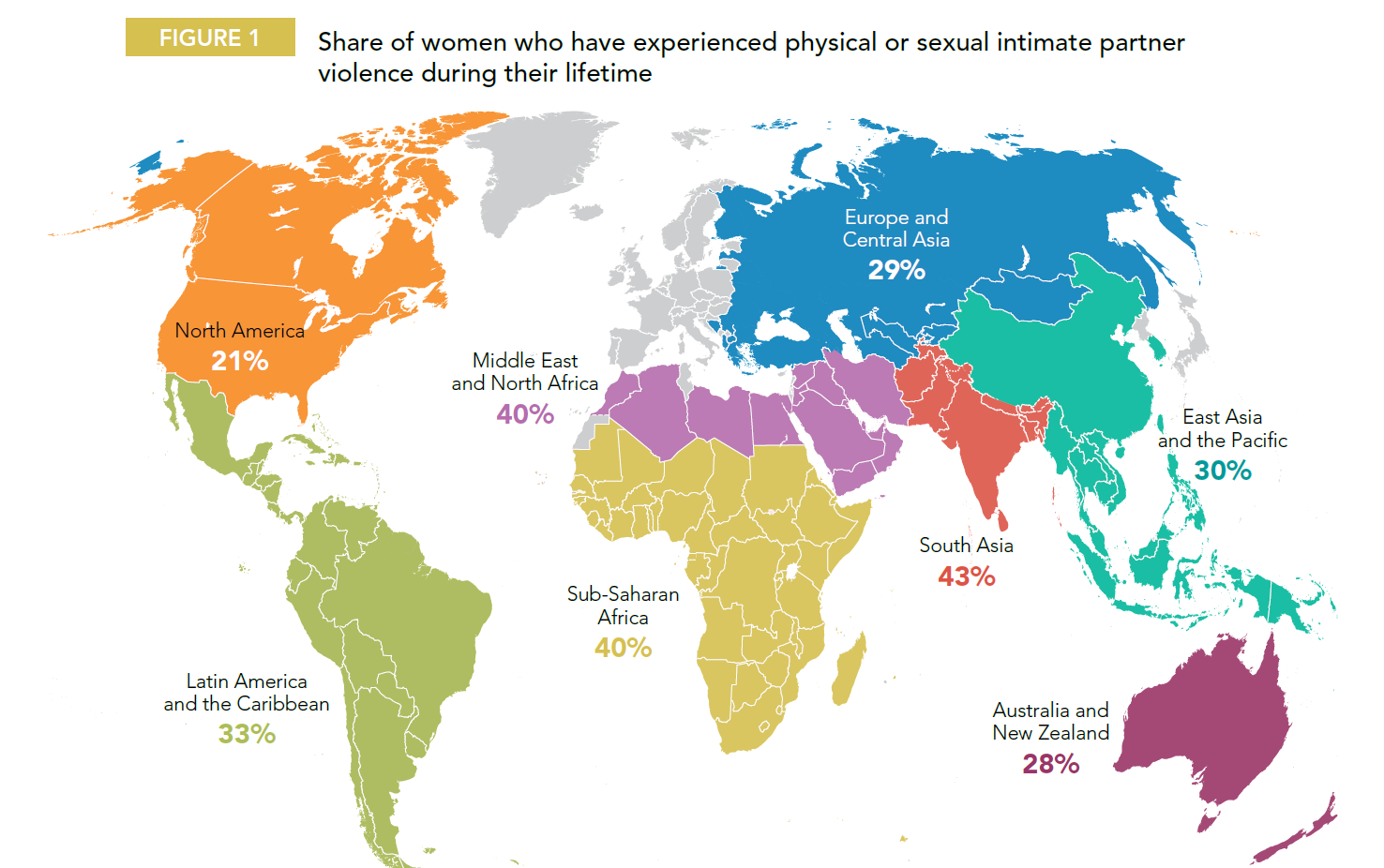

But even more striking are the hundreds of millions of women who have been battered by their husbands. The media often present violence against women as a horrific episode, or the side effect of conflict, but around the world no place is less safe for a woman than her own home. The map shows regional rates of intimate partner violence, which peak as high as 43 percent in South Asia. More than one in three women globally have been subject to physical and/or sexual violence – and in the vast majority of cases, this is at the hands of their husbands or boyfriends. While the Middle East, Africa and South Asia all have rates exceeding 40 percent, the data are clear that no country, rich or poor, has sorted this problem out.

Regional Rates of Intimate Partner Violence, Lifetime Prevalence3

Source: WHO 2013, as presented in Klugman et al 2014

The total numbers are horrifying – the number of women experiencing violence in their lifetimes amount to close to the total population of sub-Saharan Africa, and almost triple the population of the US.

There is enormous personal tragedy and human toll behind these figures. And there are major repercussions for the world of work. Exposure to intimate partner violence has been linked to a multitude of health concerns including acute injuries, chronic pain, gastro-intestinal illness and gynecological problems4. The effects on mental health are also well documented: intimate partner violence increases a woman’s risk of experiencing depression two to three-fold5.

Not surprisingly, the damage caused by violence extends to reduced economic opportunities. Recent analysis in Vietnam documents how women exposed to violence have higher absenteeism, lower productivity and lower earnings than women who are not beaten6. In Tanzania, the size of these losses was estimated to be of the order of 60 percent lower earnings7. Other studies have traced the effects on absenteeism – for example, missing seven days of paid work, on average, as a result of each violent episode8.

This underlines the economic importance of these widespread breaches of human rights, and the need to address regressive social norms and bad laws as a cornerstone of rethinking work for human development.

Jeni Klugman is a Fellow at the Women and Public Policy Program, Kennedy School Harvard University and a director of the Human Development Report Office (2008-11). Interested readers might also read Naila Kabeer’s paper on Violence against Women as well as the box article in the 2014 Human Development Report (page 75).

Notes

1For a recent comprehensive overview of global trends and patterns, see Gender at Work, 2014. World Bank: Washington DC.

2Ariane Hegewisch and Heidi Hartmann, 2014. Occupational Segregation and the Gender Wage Gap: A Job Half Done. http://www.iwpr.org/publications/pubs/occupational-segregation-and-the-gender-wage-gap-a-job-half-done

3Share of ever partnered women who have experienced physical or sexual intimate partner violence during their lifetime, using WHO global prevalence database. Equivalent rate for Europe (EU28) – not shown -- is estimated at 22 percent: http://fra.europa.eu/sites/default/files/fra-2014-vaw-survey-main-results_en.pdf

4As summarized in Klugman, Jeni; Hanmer, Lucia; Twigg, Sarah; Hasan, Tazeen; McCleary-Sills, Jennifer; Santamaria, Julieth. 2014. Voice and Agency : Empowering Women and Girls for Shared Prosperity. Washington, DC: World Bank Group.

5Beydoun, Hind A., May A. Beydoun, Jay S. Kaufman, Bruce Lo, and Alan B. Zonderman. 2012. “Intimate Partner Violence against Adult Women and Its Association with Major Depressive Disorder, Depressive Symptoms, and Postpartum Depression: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis.” Social Science and Medicine 75 (6): 959–75.

6Duvvury, Nata, Aoife Callan, Patrick Carney, and Srinivas Raghavendra. 2013. “Intimate Partner Violence: Economic Costs and Implications for Growth and Development.” 2013. Women’s Voice, Agency, and Participation Research Paper 3, World Bank, Washington, DC.

7Vyas, Seema. 2013. “Estimating the Association between Women’s Earnings and Partner Violence: Evidence from the 2008–2009 Tanzania National Panel Survey.” Women’s Voice, Agency, and Participation Research Paper 2, World Bank, Washington, DC.

8ICRW 2009. “Intimate Partner Violence: High Costs to Households and Communities.” ICRW, Washington, DC.

Photo credit: UN Women/ J Carrier

The HDialogue blog is a platform for debate and discussion. Posts reflect the views of respective authors in their individual capacities and not the views of UNDP/HDRO.