As successive Human Development Reports have shown, most people in most countries are doing better in human development. Globalization, advances in technology and higher incomes all hold promise for longer, healthier, more secure lives. But there is also a widespread sense of precariousness in the world today. Improvements in living standards can quickly be undermined by a natural disaster or economic slump. Political threats, community tensions, crime and environmental damage all contribute to individual and community vulnerability.

The 2014 Report, on vulnerability and resilience, shows that human development progress is slowing down and is increasingly precarious. Globalization, for instance, which has brought benefits to many, has also created new risks. It appears that increased volatility has become the new normal. As financial and food crises ripple around the world, there is a growing worry that people and nations are not in control over their own destinies and thus are vulnerable to decisions or events elsewhere.

The report argues that human progress is not only a matter of expanding people's choices to be educated, to live long, healthy lives, and to enjoy a decent standard of living. It is also about ensuring that these choices are secure and sustainable. And that requires us to understand – and deal with – vulnerability.

Traditionally, most analysis of vulnerability is in relation to specific risks, like disasters or conflicts. This report takes a wider approach, exploring the underlying drivers of vulnerabilities, and how individuals and societies can become more resilient and recover quicker and better from setbacks.

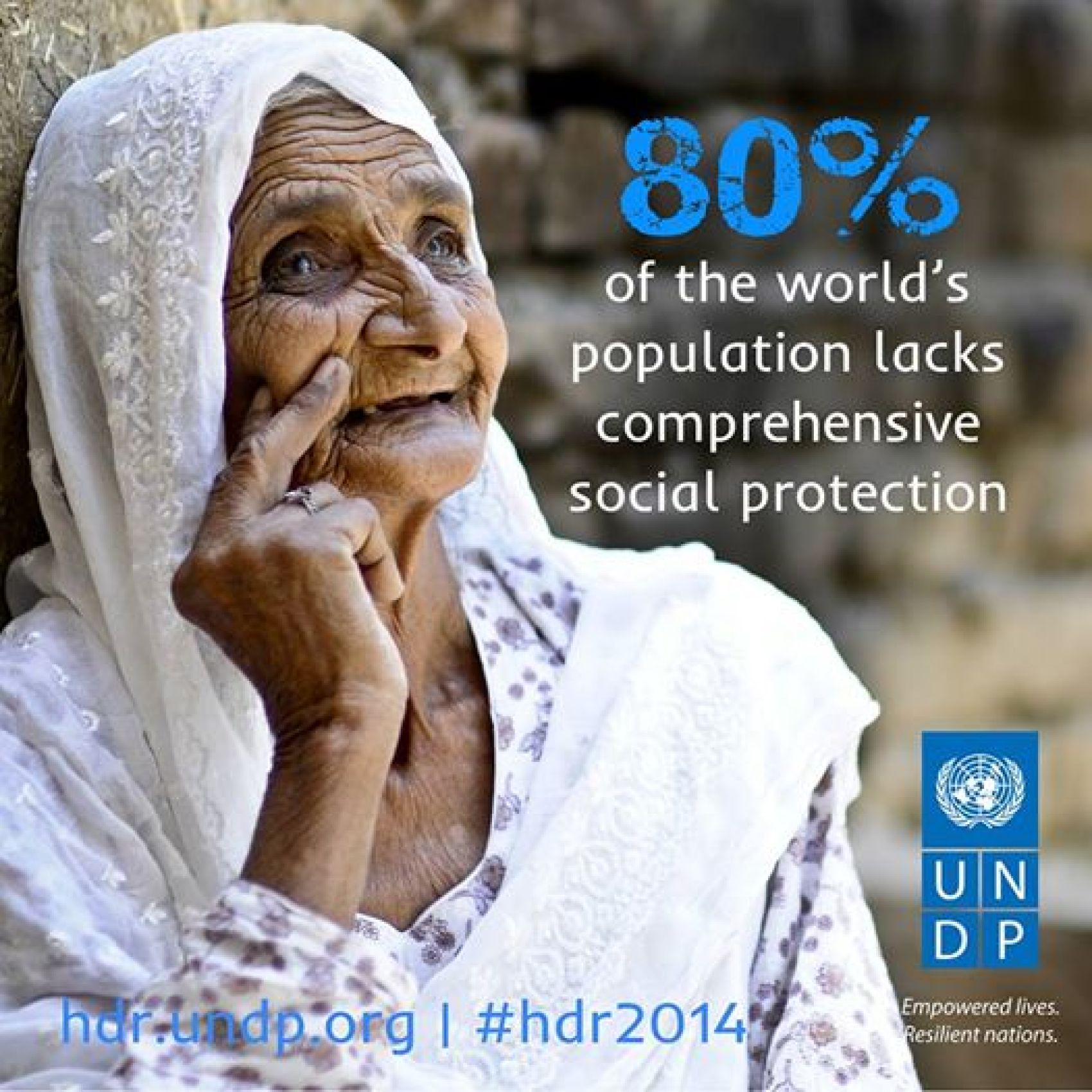

Vulnerability is a critical concern for many people. Despite recent progress, 1.5 billion people still live in multidimensional poverty. Half as many again, another 800 million, live just above the poverty threshold. A shock can easily push them back into poverty. Nearly 80 percent of the world lacks social protection. About 12 percent, or 842 million, experiences chronic hunger, and nearly half of all workers – more than 1.5 billion – are in informal or precarious employment.

More than 1.5 billion people live in countries affected by conflict. Syria, South Sudan, Central Africa Republic are just some of the countries where human development is being reversed because of the impact of serious violent conflict. We live in a vulnerable world.

The report demonstrates and builds on a basic premise: that failing to protect people against vulnerability is often the consequence of inadequate policies and poor social institutions.

And what are these policies? The report looks, for instance, at how capabilities are formed, and at the threats that people face at different stages of their lives, from infancy through youth, adulthood, and old age. Gaps in the vocabularies of children from richer and poorer families open up as early as age 3, and only widen from there. Yet most countries do not invest much in those critical early years. (Sweden is a notable, good example.) Social spending needs to be aimed where and when it is needed most.

The report makes a strong call as well for the return of full employment as a central policy goal, as it was in the 1950s and 1960s. Jobs bring social benefits that far exceed the wages paid. They foster social stability and social cohesion, and decent jobs with the requisite protections strengthen people's ability to manage shocks and uncertainty.

The report makes a strong call as well for the return of full employment as a central policy goal, as it was in the 1950s and 1960s. Jobs bring social benefits that far exceed the wages paid. They foster social stability and social cohesion, and decent jobs with the requisite protections strengthen people's ability to manage shocks and uncertainty.

Countries acting alone can do much to make these changes happen – but national action can go only so far. In an interconnected world, international action is required to make these changes stick. The provisioning of public goods – from disease control to global market regulations – are essential so that food price volatility, global recessions and climate change can be jointly managed to minimize the global effects of localized shocks.

Progress takes work and leadership. Many of the Millennium Development Goals are likely to be met by 2015, but success is by no means automatic, and gains cannot be assumed to be permanent. Helping vulnerable groups and reducing inequality are essential to sustaining development both now and across generations.

Khalid Malik is the lead author of the Human Development Report and Director of the UNDP Human Development Report Office.

This article was originally written for IPS and is available here.

The HDialogue blog is a platform for debate and discussion. Posts reflect the views of respective authors in their individual capacities and not the views of UNDP/HDRO.