Christina Lengfelder is a Research Analyst at the Human Development Report Office (HDRO) at UNDP and Margaret Carroll is a Policy Specialist at United Nations Volunteers (UNV)

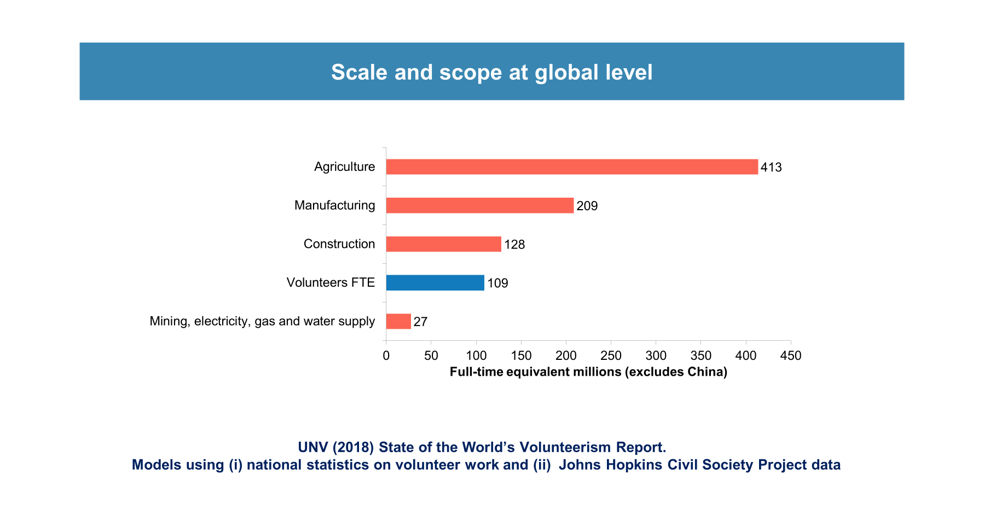

Unlike mainstream economics, the human development approach considers an agent as someone who generates change through action, instead of someone who acts on the behalf of others. Agency can be practised through social, economic and political participation, including volunteering. Millions of volunteers around the world (see figure) generate change through performing “unpaid, non-compulsory activity to produce goods or services for others”.”.

But can this agency help reduce inequalities in human development? This was the key question for a joint UNV-HDRO Seminar that gathered experts from the World Bank, UN ECLAC, ILO, the International Federation of the Red Cross, and Harvard University in New York last September. In particular, Professor Michele Lamont helped explore whether volunteering might be an important mechanism for ‘destigmatization’.

Let us first consider some background.

Even though population weighted global income inequality has decreased for a few decades now (and unweighted average Gini-coefficients have also declined for the past few years), disparities in human development, including inequalities between countries and groups are still abysmal and prevent people from realizing their full potential. Inequalities are not limited to income: they can also be found in many other areas of human development, such as health and education.

Both the technological revolution and globalization have increased understanding about inequalities. In a connected world, it is easier than ever before for people to access information on how others live in distant places or even to travel to experience those cultures for themselves. There is now probably more awareness about inequalities than ever before. Perhaps this is one of the reasons inequality has moved to the centre of the development debate, as expressed by SGD 10.

But how we see inequalities is not just about data showing disparities between people. Cultural narratives around inequalities are also very powerful. Harvard Professor Michele Lamont argues that in societies with increasing wealth concentrations and decreasing social mobility, there is a broader and more explicit understanding of ‘winners and losers’ in society. This influences perceptions of whether certain inequalities are “fair”. In some cases, vulnerability and poverty are seen as personal failings rather than structural problems, which means acceptance of some forms of inequality may increase. Support for the welfare of others can decline if members of society become alienated.

Peoples’ agency, as well as collective action and the fostering of solidarity and empathy among society is key to overcoming this view of inequalities. Recognizing the equal value of citizens requires ‘de-stigmatization’ of marginalized groups. Volunteerism, which can be seen as an expression of agency, but also as an act of collective action, can make a key contribution. Since inequalities are also associated with social distance, volunteering can bridge boundaries across social groups. It can thus reduce the alienation and isolation of specific communities, reshuffling social roles and connecting people from different backgrounds as equals. And so, volunteering could be a key pillar for reshaping cultural narratives particularly around who is a productive member of society, or challenge philanthropic models of ‘those with more, helping those with less’.

For example, with the right support and investment, volunteering can create opportunities for interaction between refugees and their new communities. There is also increasing interest in fostering a stronger understanding across generations through shared volunteer experiences, particularly in places where social segmentation and isolation is a problem. Volunteer-led committees across communities in conflict have contributed to building shared understanding and cooperation around natural resources.

In some cases, volunteerism can reinforce social and economic inequalities. Since volunteering is not remunerated, volunteer work can compete with income generating activities, while especially full-time volunteers need to be able to support themselves. Similarly, volunteer roles often reflect broader social and economic status. This can increase disparities where, for example, those able to afford to volunteer can also build up their skills and resumes. At the same time, the billions of voluntary actions each day taken by local people in their own communities have little recognition, such as women’s unpaid care work in communities.

We believe that there is a need for policies that enable people from all social strands to express agency, bridge social divides, and enjoy the benefits that come with volunteering, regardless of their background. These can include, but should not be limited to the following:

- Greater investment by national and local governments and their partners in volunteer opportunities that prioritise ‘volunteering with’, rather than ‘volunteering for’, those of a different social or economic background.

- Creating opportunities for citizens to interact and develop their own solutions to development priorities, recognizing that many people prefer to volunteer informally.

- Recognising the skills, commitment and contribution of all types of volunteers. .

- Providing universal social protection policies that ensure health and accident insurance for volunteers, thereby helping all people to express agency on a more equal basis.

Today is International Volunteer Day. Let us – as a global community –seize the opportunities that lie in volunteerism to expand agency and redress inequalities in human development.