It is no secret that the world’s population is ageing. As fertility declines and life expectancy increases, the proportion of older people is projected to grow across the world. Therefore, it is increasingly important to develop metrics that assess the effectiveness of policies and programmes affecting older people.

The 2002 Madrid International Plan of Action on Ageing (MIPAA) is central to this measurement agenda and has three priority areas:

- Older persons and development (in particular social protection);

- Advancing health and well-being into old age; and

- Ensuring enabling and supportive environments.

Fifteen years later, it is timely to assess the effectiveness of the Plan and indeed review it is a theme of this week’s UN Commission for Social Development.

The MIPAA started with great promise as one of the only international policy frameworks to focus on older people. The latest UN review of MIPAA shows that despite progress, its implementation remains uneven across both countries and the three priority areas. Major constraints include lack of resources, political will and data.

In such introspection, another critical question is how the MIPAA stays relevant when the international community is committed instead to its newest and most comprehensive policy framework to date, the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

So, what have we learned from the process?

The MIPAA experience so far offers one major lesson: its monitoring lacked a comprehensive global approach. This was partly because of lack of age-disaggregated data in many countries, but mainly because the MIPAA monitoring toolkit was not properly developed.

While there has been progress in implementing the MIPAA, there is no one approach towards its monitoring. This in turn has led to too much anecdotal, descriptive and self-defined information, with little evaluation of the relationship between outputs and policy impact, and a difficulty in comparing countries. Problems, which are perhaps unsurprising in a voluntary system.

Greater national capacities are needed in many countries: not only to design policies for the older population but also to provide guidelines in assessing progress. Guidance on data collection, including timescales for reporting, is an area where investment would have significant impacts on the success of the MIPAA. This is ever more important now that demographic ageing has taken hold within developing as well as developed countries.

Lack of age-disaggregated data has been a major constraint

Fundamental to the successful implementation of the MIPAA is reliable country-level data collection and research, areas for which there was little guidance in the MIPAA’s recommendations.

In developing countries, the lack of even basic demographic data disaggregated by age and sex is acute, and complicates tracking implementation of the MIPAA. For example, in most African countries, much available data cover only younger age groups. It is not surprising that many African countries were not represented in our Global AgeWatch Index.

In part, this is because many surveys do not collect data on older persons. USAID’s Demographic and Health Surveys and UNICEF’s Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey are two of the biggest generators of global statistics but they focus mainly on children and women under the age of 49. Why not remove the age-cap in these surveys, as has been done by South Africa?

However, a better solution would be for countries to begin collecting data using specialised surveys on older people. Iran’s new national survey on older persons, set for 2018, and the UN Multi Indicator Survey on Ageing (MISA) for Sub-Saharan Africa are good examples.

The new UN Titchfield City Group on Ageing and Age-disaggregated data provides a unique opportunity for countries to learn from each other in the collection of age-disaggregated data and monitor progress in the implementation of the MIPAA.

The MIPAA monitoring toolkit needs to be developed

I believe an investment in global assessment tools is vital if the MIPAA is to be implemented seriously. A dashboard of indicators aligned with the key priorities of the MIPAA together with an adapted Active Ageing Index (AAI) – can provide the toolkit we need to monitor MIPAA implementation.

The AAI comprises 22 indicators, organised around four domains:

- 1. Employment;

2. Social Participation;

3. Independent, healthy and secure living; and

4. Capacity and enabling environment for active ageing.

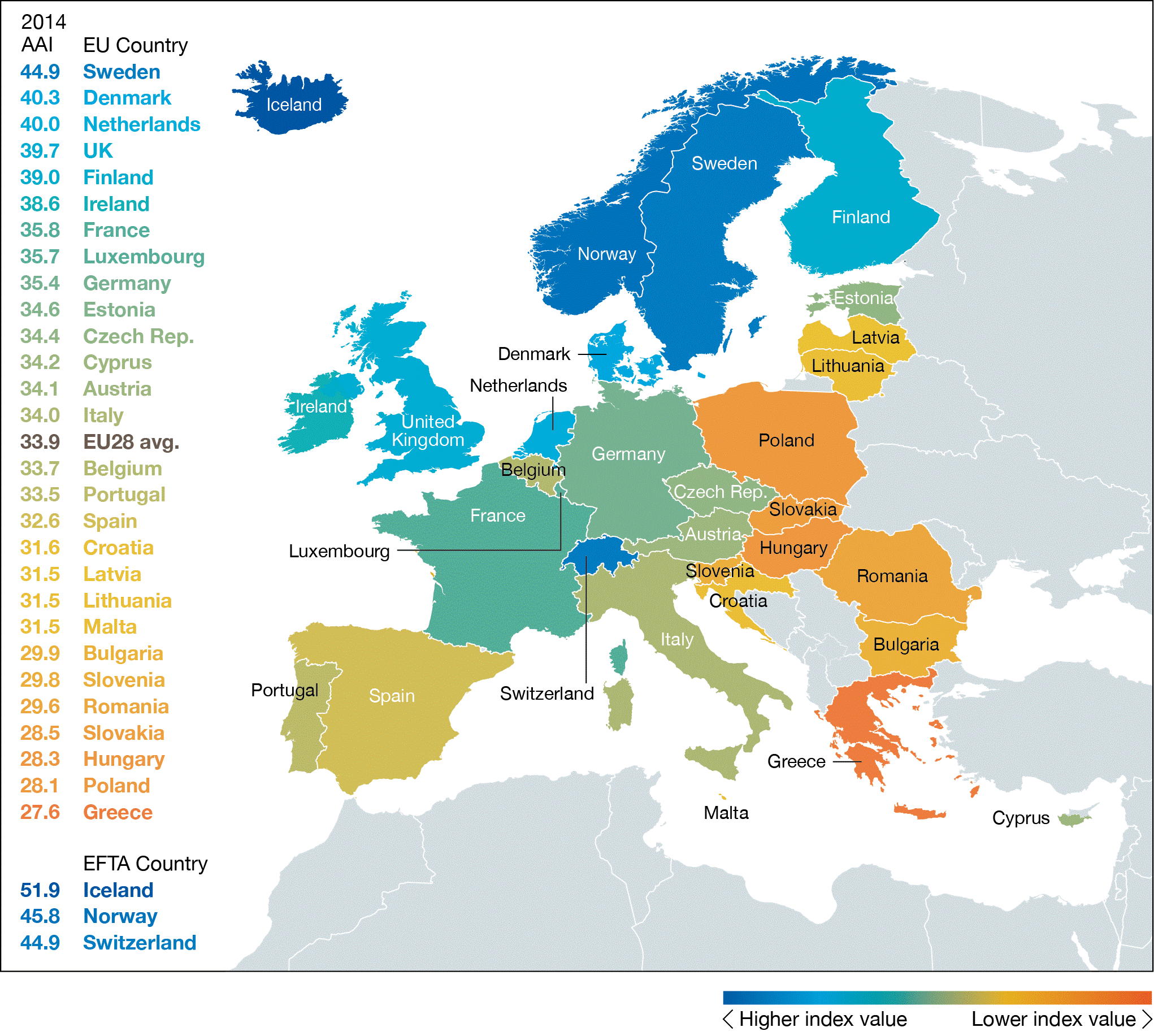

The indicators are disaggregated by gender and mainly focus on the over 55s. The AAI evidence is summarised in an aggregated country-level score, facilitating global comparisons and the production of a league table. Comparing AAI values will point out priority countries. The dashboard of indicators will identify in which areas a country is doing well (or falling short) and why. The AAI indicators were used by the UN Economic Commission for Europe in 2015, to assess the outcomes of ageing policies. The latest results for European countries show Sweden, Norway, Switzerland and Iceland at the top of the ranking, followed closely by Denmark, the Netherlands, Finland, the UK and Ireland.

Future directions for MIPAA implementation

The Sustainable Development Goals have put ageing back onto the international development agenda. The pledges to ‘Leave no one behind’ and ‘Reach the furthest behind first’, give us a strong momentum to seek inclusion of older people in all policies.

We aspire to a world in which no development process is complete without promoting the quality of life of vulnerable groups, including older people, and where the older population’s participation make them key contributors to the development process.

Ranking of European countries on the basis of the 2014 Active Ageing Index

Source: Zaidi and Stanton (2015) “Active Ageing Index 2014: Analytical Report”.

The HDialogue blog is a platform for debate and discussion. Posts reflect the views of respective authors in their individual capacities and not the views of UNDP/HDRO.

HDRO encourages reflections on the HDialogue contributions. The office posts comments that supports a constructive dialogue on policy options for advancing human development and are formulated respectful of other, potentially differing views. The office reserves the right to contain contributions that appear divisive.

Photo: UN DESA Population Division