Since its inception in 1990, the Human Development Report has turned the spotlight on wider disparities that affect people’s lives, the opportunities they enjoy, and the development prospects of their countries. Amartya Sen’s capabilities approach, the foundation stone of the HDR, emphasises a broader metric than monetary poverty for measuring progress spanning areas such as health, nutrition, gender equity and education among many others. Inequalities in such capabilities stand out as examples of what Sen has described as ‘manifest injustices’ that constitute an affront to basic ideas about fairness, justice and equality.

Child survival is a powerful illustration of those injustices: children face greater risks of mortality or malnutrition because of the wealth of their parents, the area they live in, their gender or their ethnicity. A new report by Save the Children shows the level of inequality in health outcomes and access to care, and highlights the need of equitable healthcare to drive progress on child survival.

Unfair shares and the imperative for convergence

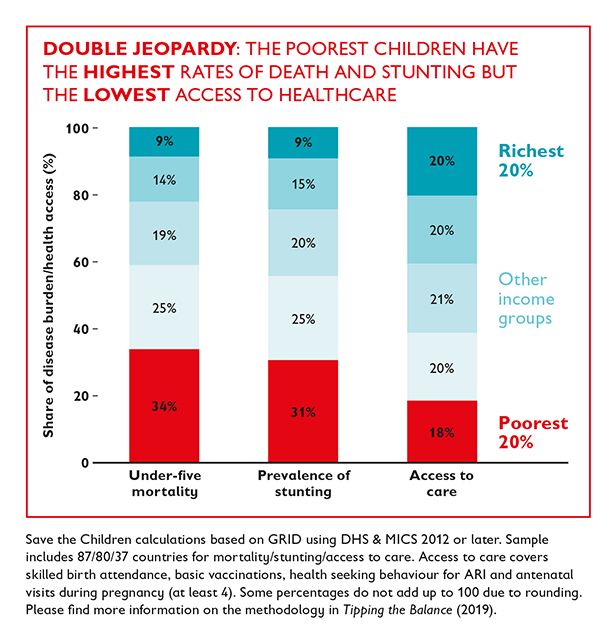

Our new evidence shows that children from the poorest 20% of households account for 34% of all child deaths and 31% of all cases of stunting. Differences in regions within countries, gender, rural/urban settings or ethnicity, both in low- and middle-income countries as well as in high-income contexts, are also powerful drivers of inequality – and determinants of a child’s chances of survival.

While the world has seen significant progress in child survival over the last decade, this progress has not been inclusive. This means we are not only far from reaching the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) on average but also failing on the pledge to Leave No One Behind. New calculations show that children from the poorest 20% of households need to see much faster progress to close the gaps with their better off peers. GRID, Save the Children’s Child Inequality Tracker, shows current inequalities as well as projections until 2030 for most low- and middle-income countries across various children’s wellbeing indicators.

The social gradient in health access and service provision

Changing this picture will require equitable access to care, which means that those groups which are further behind receive the better access to healthcare they so desperately need. However, we see a steep social gradient in access to healthcare. This leads to a double jeopardy for children: those with the highest mortality or stunting rates are those who face the lowest access to services. While children in the poorest 20% of households are responsible for about a third of child deaths and of cases of stunting, they represent only 18% of all children with access to the care they need (see graph).

Girls and boys with the highest health risks need to be at the forefront of public policies. This means ensuring that the limited resources for health and nutrition are spent in an equitable way, aligned with the health needs of children and adults. This would mean in practice, that specific groups or subnational regions with the worst child health should receive a higher share of public finances and access to health services should be prioritised for those children. However, when we compare subnational differences between child mortality and malnutrition on the one side and the capacities of health facilities to treat sick children on the other side, we find that this is not the case. More specifically, using data on service provision from Bangladesh, DRC, Malawi, Nepal, Senegal and Tanzania, we find in almost all cases that health facilities in subnational regions with higher deprivations in child health have on average lower levels of service readiness for child care. Furthermore, we find that once sick children are being treated, adherence to evidence-based guidelines are worryingly low, varying between 27% in Nepal and 38% in Senegal.

The UN Convention on the Rights of the Child sets out basic rights for every child, including the right to the highest attainable standard of health and the promise that no child is deprived of his or her right of access to health services. Universal health coverage (UHC) – where all children and their family have access to health services, vaccinations and the medicines they need, without facing financial hardship – represents that right in action. On the path towards UHC, new investments should be focused on those who are currently furthest from accessing good-quality care. Integrated Community Case Management (iCCM) was designed to deliver care in the community where children need it most, training health workers to diagnose, treat and refer major diseases. A strong focus on primary health care ensures that universal health coverage works for all, especially for the most deprived and marginalised children who need it most.